Anchoring floating wind turbines is not about brute-force resistance against the ocean; it’s a masterclass in dynamic engineering, material science, and predictive AI designed to work in symbiosis with nature’s power.

- The core challenge is managing constant motion, solved by dynamic ‘lazy wave’ cables and flexible mooring systems that absorb energy rather than fight it.

- Success depends on defeating microscopic threats like salt corrosion and integrating the variable power into the grid using sophisticated ‘synthetic inertia’ technologies.

Recommendation: For investors and engineers, success in this frontier requires shifting focus from static strength to mastering dynamic stability and predictive maintenance systems.

The image of a colossal wind turbine, its blades slicing through the air hundreds of meters above the waves, is a powerful symbol of the green energy transition. For decades, these giants have been bolted to the seabed in relatively shallow coastal waters. But the true prize, the vast and unrelenting winds of the open ocean, lies beyond the reach of conventional foundations. To harvest this immense power, the industry is pushing into deep waters, where turbines can’t be fixed; they must float. This leap confronts engineers with a monumental challenge that goes far beyond simply building a bigger base.

Many discussions about offshore wind focus on generic benefits like stronger winds or the different types of floating platforms. However, they often gloss over the brutal reality of the deep-sea environment. The fundamental question is not just how to float a 15,000-ton structure, but how to tether it to the planet in a way that it survives decades of ceaseless motion, corrosive saltwater, and hurricane-force storms. The problem is one of enduring a constant, dynamic dance with the most powerful forces on Earth.

This article moves beyond the basics to tackle the core engineering paradoxes. We will not be exploring how to fight the ocean, but rather how to design systems that elegantly coexist with its power. The key is not found in rigid resistance but in engineered flexibility, predictive intelligence, and a molecular-level understanding of material science. From the serpentine ballet of high-voltage cables on the ocean floor to the AI that predicts safe weather windows for maintenance, we will dissect the critical innovations that make deep-water wind energy possible.

This guide delves into the specific, high-stakes engineering decisions that define the success or failure of a deep-water floating wind project. We will explore the technical nuances of foundation choice, power transmission, and the critical strategies for grid integration and long-term operational viability.

Summary: Unlocking Deep-Water Wind: The Engineering of Floating Turbine Anchors

- Why Is a Sea Turbine Twice as Efficient as a Land Turbine?

- How to Run High Voltage Cables on the Ocean Floor?

- Monopile or Floating Base: Which to Choose for 100m Depth?

- The Salt Mistake That Can Seize Turbine Gears in Months

- When to Send the Crew: Using AI to Predict Weather Windows?

- How to Run Continuous Electrolyzers With Variable Wind Power?

- How to Balance French Nuclear With German Wind?

- How to Structure Electricity Tariffs to Encourage Decarbonization?

Why Is a Sea Turbine Twice as Efficient as a Land Turbine?

The primary driver for venturing into the hostile offshore environment is a simple, powerful fact: energy output. A sea-based turbine can be dramatically more efficient than its land-based counterpart, often generating power at capacity factors exceeding 60%, compared to 35-45% onshore. This isn’t just because the wind is “stronger.” It’s about the quality and consistency of the wind. Over the open ocean, wind flows are smoother, more consistent, and less subject to the turbulence created by terrestrial obstacles like hills, buildings, and forests. This laminar flow allows turbine blades to operate at their optimal aerodynamic efficiency for longer, sustained periods.

This higher efficiency translates directly into a lower levelized cost of energy (LCOE) over the turbine’s lifespan. More consistent production means more predictable revenue for investors and a more reliable power source for the grid. The case of Hywind Scotland, the world’s first commercial floating wind farm, serves as a powerful real-world example. Operational since 2017, its five 6-MW turbines mounted on spar-buoy platforms consistently achieve high capacity factors, proving the commercial viability and superior performance of tapping into the potent, stable winds far from shore. This consistent, high-volume energy production is the fundamental economic justification for tackling the immense engineering challenges of the deep sea.

How to Run High Voltage Cables on the Ocean Floor?

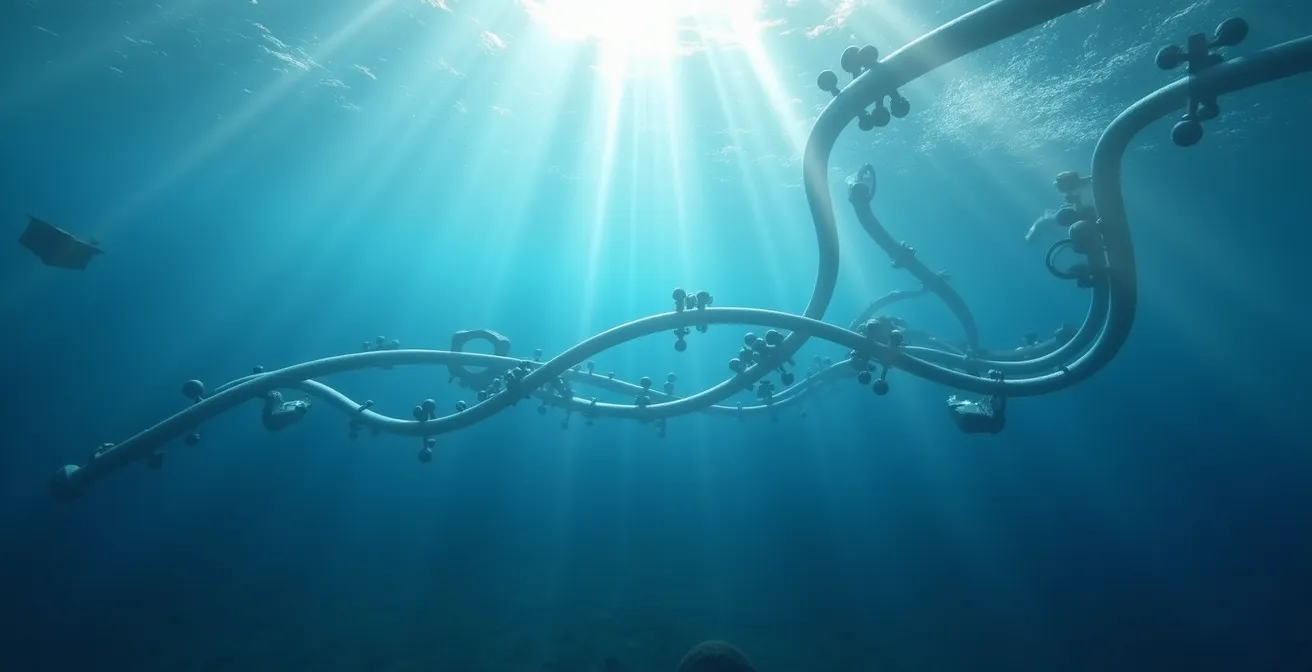

Transmitting hundreds of megawatts from a constantly moving platform to a fixed point on the seabed is one of the most complex challenges in floating wind. A simple, taut cable would snap under the strain of wave, wind, and current-induced motion. The solution lies in a concept known as the “dynamic cable” and its sophisticated configurations. These are not just insulated wires; they are complex engineering assemblies designed for decades of flexing, stretching, and twisting in a highly corrosive environment. The most common configuration is the “lazy wave,” an elegant but highly engineered solution.

In this design, the cable drops from the floating platform, is supported by a series of submerged buoyancy modules that lift it into a gentle arc, and then descends again to the seabed. This “S” shape provides the necessary slack to absorb the platform’s vertical (heave) and horizontal (surge and sway) movements without putting excessive stress on the cable or its connection points. These cables are heavily armored to resist abrasion and protect the high-voltage cores within. This engineering is essential, especially as an analysis from the Center for Sustainable Systems indicates that more than 58% of U.S. technical wind resources lie in waters deeper than 60 meters, where floating solutions and their dynamic cables are the only option.

The design of this system is a masterclass in hydrodynamics and material science. Engineers must model the vortex-induced vibrations and fatigue loads the cable will experience over millions of cycles. The connection points, known as bend stiffeners, are critical components that prevent the cable from kinking at the fixed and floating terminations. Mastering this underwater ballet of cables is fundamental to connecting the immense power of the deep ocean to the grid.

Monopile or Floating Base: Which to Choose for 100m Depth?

At a water depth of 100 meters, the choice between a fixed-bottom and a floating foundation ceases to be a simple preference and becomes a question of fundamental physics and economics. Fixed-bottom foundations, such as monopiles or jackets, have been the workhorses of the offshore industry in shallower waters (typically up to 50-60 meters). However, as depth increases, the amount of steel required for a fixed structure, and the complexity of its installation, grows exponentially. A jacket foundation for 100 meters would be a monumental steel structure, requiring highly specialized, and extremely expensive, heavy-lift vessels for installation.

This is where floating platforms become not just an alternative, but the only viable solution. They decouple the turbine’s foundation from the seabed, using a system of mooring lines and anchors instead of a rigid steel tower. This fundamentally changes the cost equation. While the floating platform itself is a complex piece of equipment, its cost does not scale exponentially with water depth in the same way a fixed foundation does. Furthermore, floating platforms offer a significant logistical advantage: the entire assembly—platform and turbine—can be put together in a controlled port environment and towed out to the site, drastically reducing the need for risky and weather-dependent offshore heavy-lift operations.

The following table, based on extensive industry analysis, outlines the stark differences between these two approaches when faced with the challenge of a 100-meter depth.

| Criteria | Fixed-Bottom (Jacket) | Floating Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Installation Complexity | Very High – Requires specialized vessels | Moderate – Can be assembled onshore and towed |

| CAPEX at 100m | Exponentially increasing with depth | More stable cost curve |

| O&M Requirements | Lower – Fixed structure | Higher – Mooring line inspections needed |

| Decommissioning | Complex and costly removal | Simpler – Can be towed back to port |

| Seabed Dependency | Highly dependent on soil conditions | Less sensitive to seabed type |

For investors and project developers, the data is clear. At 100 meters, the technical and financial hurdles of fixed foundations become insurmountable. The future of deep-water wind energy is unequivocally reliant on the successful deployment of floating technology.

The Salt Mistake That Can Seize Turbine Gears in Months

While structural integrity against storms is a visible challenge, a far more insidious threat operates at a microscopic level: salt. The fine, aerosolized mist of saltwater is a relentless enemy of high-performance machinery. A critical mistake in nacelle design is underestimating its ability to infiltrate sealed components. If even trace amounts of this saline mist get inside a gearbox, it can lead to catastrophic failure. Salt contaminates lubricants, drastically reducing their effectiveness and accelerating wear. More dangerously, it promotes galvanic corrosion, an electrochemical process that occurs when two dissimilar metals are in contact in the presence of an electrolyte—like saltwater. This can seize bearings and destroy gears in a matter of months, not years.

Protecting the multi-million-dollar drivetrain housed in the nacelle requires a multi-layered defense system. It’s not just about seals and gaskets; it’s about managing the entire internal environment. This includes sophisticated air filtration systems for the HVAC units, maintaining positive air pressure within the nacelle to push contaminants out, and deploying sacrificial anodes *inside* the nacelle, not just on the external structure. The battle is fought on a chemical and atmospheric level.

The margin for error is zero. The cost of a major component replacement hundreds of meters in the air and miles out to sea is astronomical. Therefore, preventing salt ingress is one of the highest priorities in offshore turbine design. It requires a paranoid level of attention to detail, from the choice of materials to the continuous monitoring of lubricant purity.

Action Plan: Preventing Salt-Induced Turbine Failure

- Implement multi-stage air filtration systems with HEPA filters in nacelle HVAC units to capture fine salt aerosols before they enter.

- Install insulating gaskets between all dissimilar metals to break the electrical circuit required for galvanic corrosion.

- Deploy sacrificial anodes strategically inside the nacelle to protect critical steel components, in addition to external protections.

- Monitor lubricant contamination with real-time sensors capable of detecting saline presence in parts-per-million, triggering early warnings.

- Maintain a slight positive pressure within sealed gearboxes and other critical enclosures to actively prevent salt mist infiltration.

- Conduct regular oil sampling and analysis as a secondary verification method for early detection of salt contamination.

When to Send the Crew: Using AI to Predict Weather Windows?

Operations and Maintenance (O&M) are the lifeblood of a wind farm’s profitability, but in the offshore environment, O&M is dictated by the weather. Sending a crew to a turbine requires wave heights to be below a certain threshold (typically 1.5-2.0 meters) for a safe transfer from the vessel to the turbine ladder. Missing these “weather windows” means costly downtime and underutilized crews. In fact, comprehensive NREL analysis demonstrates that weather-related delays account for up to 30% of O&M downtime in offshore wind. This is a massive drain on a project’s bottom line.

The traditional approach of relying on standard marine forecasts is often too coarse. A regional forecast might predict rough seas for an entire day, leading to a cancelled mission, when in reality a safe 3- or 4-hour window might exist at the precise turbine location. This is where predictive intelligence becomes a game-changing tool. Modern offshore wind farms are moving beyond reactive scheduling to proactive, AI-driven prediction.

Case Study: Hyper-Local Forecasting for O&M Optimization

Modern offshore wind farms are now deploying their own sensor arrays, including wave buoys and nacelle-mounted Lidar systems, to gather immense amounts of hyper-local environmental data. This proprietary data stream feeds into sophisticated AI models. These models learn the unique micro-weather patterns of the wind farm and can predict safe maintenance windows with a level of accuracy unattainable by public forecasts. By identifying short, viable 3-hour windows that would otherwise be missed, these systems significantly improve crew and vessel utilization, boost turbine availability, and enhance the safety of offshore technicians.

This shift from relying on general forecasts to creating proprietary, high-resolution predictions is fundamental to optimizing deep-water operations. It transforms weather from an uncontrollable variable into a manageable risk, allowing operators to surgically target maintenance activities and maximize energy production.

How to Run Continuous Electrolyzers With Variable Wind Power?

Pairing offshore wind with green hydrogen production is a compelling vision, but it presents a major engineering conflict: wind power is inherently variable, while industrial-scale electrolyzers, which split water into hydrogen and oxygen, operate most efficiently and have the longest lifespan when run continuously. Subjecting an electrolyzer to the constant ramps up and down of a wind turbine would drastically reduce its efficiency and could damage it over time. The challenge is to create a rock-steady power supply from an intermittent source.

There is no single solution; rather, it requires a system of systems. The first and most brute-force approach is massive oversizing. To guarantee a constant power supply for a given hydrogen output, industry calculations show that systems must be oversized by 2-3 times the nominal electrolyzer capacity. This ensures that even in periods of lower wind, there is enough generation to meet the electrolyzer’s demand. The excess power generated during high winds can be stored or curtailed.

However, oversizing alone is not enough. A sophisticated power-smoothing and energy-buffering architecture is required. This involves several key technologies working in concert:

- Battery Systems: Large-scale batteries are deployed for millisecond-to-minute scale power smoothing. They absorb sudden gusts and fill in short lulls, shielding the electrolyzer from rapid fluctuations.

- Energy Buffers: To manage longer periods of low wind (hours or days), a large energy buffer is essential. This is typically in the form of stored hydrogen itself, kept in pressurized tanks or vast underground salt caverns.

- Advanced Electrolyzers: The technology of the electrolyzer itself is critical. Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) electrolyzers are favored for this application as they can operate over a much wider power range (e.g., 20% to 110% of nominal capacity) compared to older alkaline technologies.

- Power Electronics: Sophisticated DC-DC converters are the final gatekeepers, ensuring that the current delivered to the delicate electrolyzer stacks is perfectly stable, regardless of the chaos on the generation side.

Creating a continuous hydrogen factory powered by the wind is a formidable task of system integration. It requires a holistic design that combines raw power, high-speed electronics, and large-scale chemical storage.

How to Balance French Nuclear With German Wind?

On a continental scale, the grid faces a monumental balancing act. It must integrate the highly variable, intermittent power from sources like German offshore wind with the steady, high-inertia baseload power from sources like the French nuclear fleet. Historically, the grid’s stability—its ability to maintain a constant frequency (50 Hz in Europe)—has relied on the physical inertia of massive, spinning turbines in traditional power plants (nuclear, coal, gas). As these are replaced by renewables, which are connected to the grid via power electronics with no physical inertia, the grid becomes more fragile and susceptible to frequency deviations that can lead to blackouts.

The solution is not to curtail wind, but to make wind power “smarter.” The breakthrough technology enabling this is the grid-forming inverter. Unlike traditional “grid-following” inverters that simply inject power into a stable grid, grid-forming inverters can create their own voltage and frequency reference. They can actively respond to grid disturbances, injecting or absorbing power in milliseconds to counteract frequency drops or spikes. In essence, they use software to create “synthetic inertia,” perfectly mimicking the stabilizing effect of a multi-ton spinning generator.

This technology is critical for a future high-renewables grid. It allows a wind farm to transform from a passive power source into an active grid stabilizer. This is not a distant future technology; it is being deployed now. As ambitious targets are set, such as the Marienborg Declaration’s goal for 19.6 GW of offshore wind in the EU’s Baltic Sea by 2030, the ability of these new assets to provide stability services becomes paramount. A wind farm equipped with grid-forming inverters can help balance the grid, reduce reliance on fossil-fuel-based stabilizers, and ensure a secure electricity supply even as the share of renewables soars.

Key Takeaways

- Offshore wind’s superiority lies in consistent, high-capacity power generation, not just stronger winds, enabling a more reliable energy supply.

- Engineering for the deep sea requires embracing dynamic stability through flexible systems like ‘lazy wave’ cables, rather than relying on rigid resistance.

- Smart technologies, from predictive AI for maintenance to grid-forming inverters for stability, are as critical to success as the physical steel structure.

How to Structure Electricity Tariffs to Encourage Decarbonization?

Ultimately, the colossal steel structures and sophisticated electronics of offshore wind must be integrated into a market that encourages their use. Traditional electricity tariffs, with flat or simple time-of-use rates, are ill-suited for a grid dominated by renewables. They do not provide the right signals to encourage consumption when green energy is abundant and cheap, or discourage it when it is scarce and fossil-fuel backup is required. To accelerate decarbonization, tariff structures must become as dynamic as the weather itself.

Several innovative tariff models are emerging to solve this. These are not just pricing mechanisms; they are powerful tools for shaping demand to match renewable supply. For large industrial consumers, these tariffs can turn them into “virtual power plants,” paying them to shift their consumption and help stabilize the grid. For residential customers, they can automate smart appliances to run when wind is blowing, reducing both their bills and the grid’s carbon footprint. The goal is to create a transparent, real-time link between generation and consumption.

This table outlines some of the most promising tariff structures that are critical for integrating massive new sources of renewable energy.

| Tariff Type | Mechanism | Decarbonization Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Intensity Pricing | Real-time pricing linked to grid carbon content | Shifts demand to high renewable periods |

| Nodal/Locational Pricing | Location-specific prices reflecting congestion | Incentivizes renewable development where needed |

| Demand Response Tariffs | Payment for consumption flexibility | Industrial users act as virtual power plants |

| Time-of-Use with Wind Signal | Lower prices during high wind generation | Aligns consumption with renewable availability |

Implementing these smart tariffs is a regulatory and technological challenge, but it is essential for maximizing the value of assets like deep-water wind farms. As ambitious goals are set, such as the projection that wind could provide 35% of U.S. electricity by 2050, these market mechanisms become the invisible infrastructure that makes a decarbonized grid possible.

The frontier of deep-sea energy is not just about building turbines; it’s about architecting the future of a resilient, decarbonized global grid. Engaging with these advanced engineering and economic principles is the first step toward mastering it.