An EV battery’s “death” is not an end but a critical fork in the road, where engineering and ethics determine its path from hazardous waste to a valuable resource.

- The true environmental and human cost of an EV is tied to its battery, especially the sourcing of materials like cobalt and the risks of improper disposal.

- A circular economy approach—prioritizing repurposing, repair, and advanced recycling—can close the loop, reducing reliance on new mining and creating new economic value streams.

Recommendation: Shift your perspective from a simple consumer to an informed stakeholder. The most sustainable battery is not just one that is recycled, but one that was designed from the start to be repaired, repurposed, and efficiently dismantled.

The decision to drive an electric vehicle often stems from a desire to reduce one’s environmental impact. It feels like a clean choice. Yet, a nagging question lingers for the environmentally conscious consumer: what happens to the massive battery pack when the car reaches the end of its road? This question pulls back the curtain on a complex world of global supply chains, human rights, and sophisticated engineering. The common answer, “they get recycled,” is a vast oversimplification that papers over the ethical and technical challenges involved.

Many discussions focus on the simple act of recycling, but this overlooks the bigger picture. The true story of a battery’s end-of-life is a story about design. It begins not at the scrapyard, but on the engineer’s drawing board. If the fundamental challenge of battery sustainability lies in its materials and construction, then the solution must also be found there. The prevailing “take-make-dispose” model, even with a recycling step tacked on at the end, is inefficient and fails to address the root problems, including the controversial mining of raw materials.

But what if we re-engineered the entire system? This is where the principles of a circular economy offer a more responsible and ultimately more profitable path. The central idea is to shift our thinking: an old battery is not waste to be managed, but a valuable asset—a dense repository of materials and stored energy. This perspective transforms the end-of-life problem into a series of opportunities: for second-life applications, for modular repair, and for creating high-purity materials that feed directly back into new production. This article explores that journey, moving beyond the simple question of “what happens” to investigate how a systemic, design-led approach can create a truly sustainable battery lifecycle.

This guide unpacks the entire lifecycle of an EV battery, from the ethical dilemmas at its origin to the innovative business models emerging from its “waste.” We’ll explore the critical choices and engineering solutions that determine whether an old battery becomes a liability or a valuable asset.

Summary: The Complete Lifecycle of an EV Battery

- Why Is Cobalt Mining a Human Rights Issue?

- How to Repurpose Old Car Batteries for Home Solar Storage?

- Pyrometallurgy or Hydrometallurgy: Which Recycles More Material?

- The Disposal Mistake That Causes Garbage Truck Fires

- How to Design Packs That Robots Can Dismantle?

- New or Used EV: How to Spot a Degraded Battery Before Buying?

- How to Design Products That Can Be Repaired in 5 Minutes?

- How Can Small Businesses Profit From Waste Streams?

Why Is Cobalt Mining a Human Rights Issue?

The journey of an EV battery begins long before it’s installed in a car. It starts deep underground, often in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where a significant portion of a key ingredient is sourced. According to recent data, approximately 70% of the world’s cobalt is sourced from the DRC, a region fraught with political instability and severe human rights concerns. A large part of this mining is “artisanal,” a term that masks the grim reality of workers, including children, digging by hand in dangerous, unregulated conditions for meager pay. This is the ethical paradox at the heart of the green transition: the drive for cleaner air in our cities can be directly linked to hazardous labor practices thousands of miles away.

This reliance on ethically compromised materials creates a powerful incentive for a circular economy. If we can recover the cobalt already present in millions of existing batteries, we can reduce our dependence on new mining. This creates what is known as an “ethical sourcing loop.” As the Avery Dennison Research Team notes in their EV Battery Industry Report, “By recapturing rare earth metals, contribution is made to closed loop recycling.” This isn’t just an environmental goal; it’s a humanitarian one. Every gram of recycled cobalt is a gram that doesn’t need to be extracted under questionable conditions.

Recognizing this challenge, some governments are stepping in to formalize the end-of-life process and ensure that valuable materials are channeled correctly.

Case Study: China’s Battery Recycling “White List” Program

Since 2018, China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has taken a proactive stance by issuing “white lists” of approved power-battery recyclers. This program, now including 156 companies, demonstrates how government regulation can create a structured system for battery waste. An analysis in the MIT Technology Review highlights how this steers batteries toward certified facilities with higher standards, rather than informal operations that might perpetuate environmental or labor issues. The white list provides a clear framework for responsible end-of-life management, a model that could be adapted globally.

Closing this loop through robust recycling and repurposing is not just a technical challenge but a moral imperative for the entire EV industry.

How to Repurpose Old Car Batteries for Home Solar Storage?

When an EV battery can no longer provide the range and performance required for driving—typically when its capacity drops below 70-80%—it is far from “dead.” It enters the next phase of the circular economy: second life. These batteries retain a substantial amount of energy storage capacity, making them ideal for less demanding, stationary applications. The most promising of these is home energy storage, where they can be paired with residential solar panel systems. In this role, they store excess solar energy generated during the day for use at night, reducing reliance on the grid and maximizing the value of the solar investment.

The potential scale of this solution is immense. Research suggests that by 2030, the volume of discarded EV batteries could be so large that they could cover the entire global demand for stationary energy storage. This transforms a looming waste problem into a massive distributed energy resource, enhancing grid stability and accelerating the adoption of renewable energy. For homeowners, it offers a more affordable path to energy independence, as repurposed batteries are significantly cheaper than new, purpose-built storage systems.

As this image shows, the concept is already a reality. Companies and even DIY enthusiasts are engineering systems to convert modules from used EV packs into sleek, wall-mounted units. The key is a sophisticated Battery Management System (BMS) that can safely manage the charging and discharging of these second-life cells. Several automakers are leading the charge, creating certified programs to ensure safety and reliability.

Case Study: Nissan’s 4R Energy Second-Life Program

A joint venture between Nissan and Sumitomo, 4R Energy, has streamlined the process of evaluating used EV batteries for their second-life potential. The company developed technology to assess a full pack of 48 modules simultaneously, slashing the diagnostic time from two weeks to a single day. This efficiency is critical to making second-life applications economically viable. The company’s motto of “Reuse, Resell, Refabricate and Recycle” perfectly encapsulates the circular hierarchy, ensuring that every battery’s potential is maximized before it is sent for material recovery.

This step not only extends the battery’s useful life but also provides significant environmental and economic benefits before the final stage of recycling even begins.

Pyrometallurgy or Hydrometallurgy: Which Recycles More Material?

When a battery can no longer be repurposed, it finally reaches the true end of its life and enters the recycling phase. Here, the goal is to break it down and recover the valuable materials within, like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. However, not all recycling methods are created equal. The two dominant industrial processes, pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy, have vastly different outcomes in terms of material recovery and environmental impact. Understanding this difference is key to assessing the true sustainability of the recycling chain.

Pyrometallurgy is essentially a brute-force approach. It involves shredding the battery packs and smelting them in a furnace at extremely high temperatures (1200-1450°C). While this process can recover some valuable metals like cobalt and nickel, it has major drawbacks. The intense heat destroys the lithium, aluminum, and manganese, which end up in a waste byproduct called slag. It is also incredibly energy-intensive and releases harmful emissions. In contrast, hydrometallurgy is a more refined, chemical-based process. The batteries are dissolved in a solution, and various chemical reactions are used to precipitate and isolate each metal with a high degree of purity. This method can recover up to 95% of the valuable materials, including the lithium that pyrometallurgy loses.

A third, emerging method known as direct recycling goes a step further. It aims to remove and refurbish the cathode material—one of the most complex and valuable components of the battery—without breaking it down to its elemental level. This preserves the material’s intricate structure and requires far less energy to turn it back into a new battery. The following table, based on an analysis from the Union of Concerned Scientists, compares these methods.

| Method | Material Recovery | Environmental Impact | Process Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrometallurgy | High recovery rates for all metals | Low environmental impact | Uses chemical solutions to isolate metals |

| Pyrometallurgy | Loses lithium, aluminum, manganese | Highest environmental impact | Smelting at 1200-1450°C |

| Direct Recycling | Recovers cathode intact | Low environmental impact | Preserves material structure |

From an engineering and environmental standpoint, the industry’s shift toward hydrometallurgy and direct recycling is essential for creating a truly closed-loop system where material integrity is preserved and waste is minimized.

The Disposal Mistake That Causes Garbage Truck Fires

While the focus is often on the sophisticated end of the battery lifecycle, a critical danger lies in the very first step of disposal: human error. A lithium-ion battery, even one that’s considered “dead,” still retains a significant amount of residual energy. This stored energy makes it extremely dangerous if handled improperly. The single biggest mistake is treating an EV battery—or any lithium-ion battery from a device like a laptop or power tool—as regular waste.

When a battery is thrown into a standard trash or recycling bin, it’s a ticking time bomb. The battery can be easily punctured or crushed during collection and transport, leading to a short circuit. This triggers a process called thermal runaway, a rapid and unstoppable chain reaction where the battery’s temperature skyrockets, causing it to vent flammable, toxic gases and burst into violent flames. These fires are notoriously difficult to extinguish and are a growing cause of fires in garbage trucks and waste management facilities. As the US Environmental Protection Agency warns, “Fires at end of life are common and mismanagement and damage to batteries make them more likely at that stage.”

Fires at end of life are common and mismanagement and damage to batteries make them more likely at that stage.

– US Environmental Protection Agency, EPA Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling Guidelines

Because of this inherent hazard, end-of-life EV batteries are often classified as hazardous waste. They must never be mixed with household trash. The proper disposal channel involves specialized logistics and certified facilities equipped to handle them safely. For consumers, this means contacting the vehicle dealership, an authorized service center, or a certified battery recycler to arrange for a take-back.

Your Action Plan for Safe Battery Handling

- Identify all contact points: Never place EV batteries in regular trash or recycling bins. Recognize them as a separate, hazardous waste stream.

- Inventory existing protocols: Contact your EV dealership or certified auto service centers to understand their specific take-back programs for end-of-life batteries.

- Ensure consistency with regulations: The battery must be managed as universal or hazardous waste. Confirm the facility you are using is certified to handle this classification.

- Assess safety and storage: If you must store the battery temporarily, keep it in a designated, dry outdoor area away from flammable materials and direct sunlight to prevent overheating.

- Plan for integration: Ensure the battery is properly packaged for transport according to the recycler’s guidelines to prevent damage or short circuits en route.

Proper handling is the first and most important step in ensuring that a battery’s end-of-life journey is a safe one.

How to Design Packs That Robots Can Dismantle?

The most significant bottleneck in battery recycling is not the chemistry, but the physics: taking the battery pack apart. A typical EV battery is a fortress, containing hundreds or thousands of individual cells that are welded, glued, and sealed together for durability and safety during the vehicle’s operational life. This robust construction becomes a major obstacle at the end of its life. Manual disassembly is slow, expensive, and dangerous for human workers due to the high voltages and hazardous materials involved. This is where the principle of Design for Disassembly (DfD) becomes paramount.

DfD means engineering the battery pack from day one with its eventual deconstruction in mind. This involves a shift from permanent bonding to mechanical fastening. Instead of strong adhesives, designers can use bolts, clamps, and standardized connectors. This creates a modular architecture where cell groups, the BMS, and other components can be easily and quickly separated. Such a design is not only safer for human workers but also opens the door for robotic disassembly. Robots can work faster, more precisely, and without risk, drastically reducing the cost and time required to prepare batteries for recycling or repurposing.

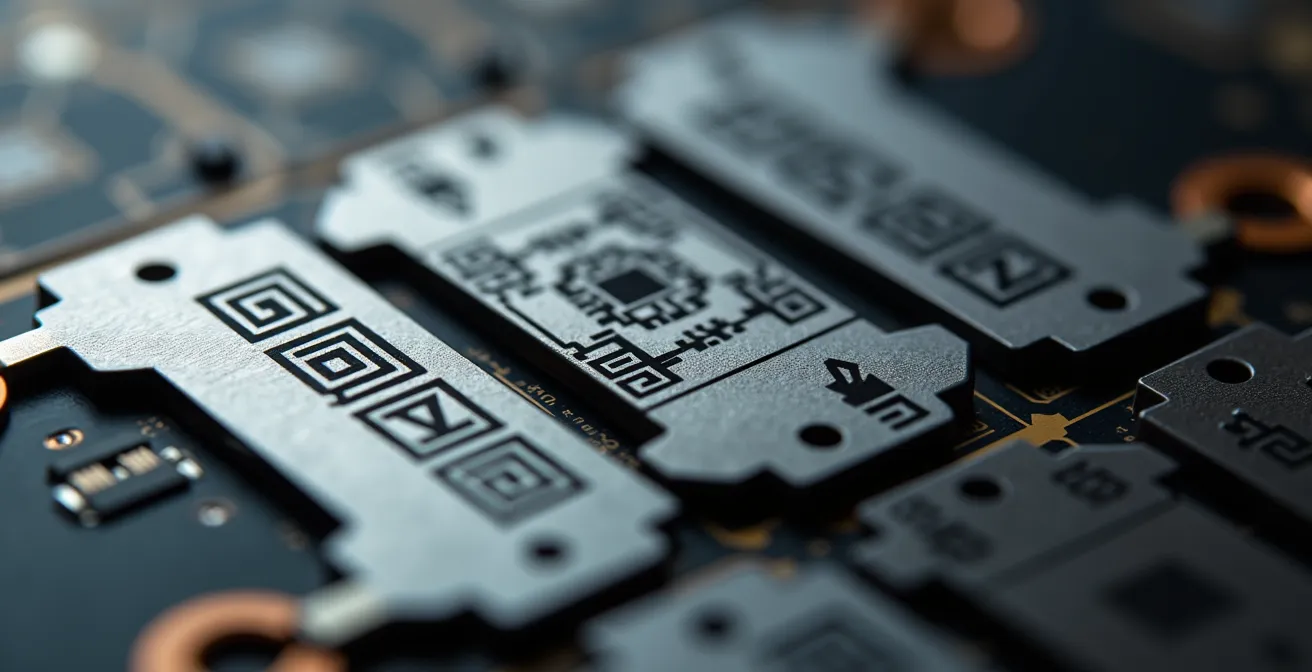

This close-up view illustrates the concept: precision connectors and modular locking mechanisms that can be easily manipulated by an automated system. Some designs even incorporate etched patterns, like QR codes, that a robot can scan to identify the specific module type and apply the correct disassembly procedure. The ultimate vision for DfD is a battery that can almost take itself apart.

Case Study: MIT’s Self-Assembling (and Disassembling) Material

Pushing the boundaries of DfD, researchers at MIT developed a groundbreaking self-assembling material that could serve as a solid-state battery’s electrolyte. As detailed in a paper in *Nature Chemistry*, this material functions perfectly as the connecting layer in a working battery. However, when submerged in a specific organic liquid, it rapidly breaks down into its original molecular components. Because the electrolyte is what holds the battery together, this process causes the entire cell to disassemble in minutes. This innovation shows how material science can be harnessed to design a battery that dismantles on command, radically accelerating the recycling process.

By embedding end-of-life considerations into the initial design phase, engineers can turn the biggest challenge in battery recycling into a streamlined, automated solution.

New or Used EV: How to Spot a Degraded Battery Before Buying?

For a prospective EV buyer, particularly one considering a used vehicle, the battery is the single most important and expensive component. Its health directly dictates the car’s range, performance, and ultimate value. While EV batteries are designed to be durable—with some Teslas having traveled more than 400,000 miles on their original pack—all batteries degrade over time. Knowing how to assess this degradation is crucial to making a smart purchase and avoiding a costly replacement down the line.

The most important metric is the battery’s State of Health (SoH), which is a measurement of its current maximum capacity relative to its original capacity when new. A brand-new battery has an SoH of 100%. Over time, due to factors like age, cycle count, and charging habits, this number will decrease. While the car’s dashboard provides a range estimate, this figure can be misleading as it’s often influenced by recent driving style and temperature. It is not a direct measure of SoH.

To get a true reading, a more technical approach is needed. The best method is to use an OBD2 (On-Board Diagnostics) scanner paired with a specialized smartphone app (like LeafSpy for Nissan Leafs or Teslaspy for Teslas). This tool plugs into the car’s diagnostic port and communicates directly with the Battery Management System (BMS) to retrieve the raw SoH percentage. This gives you an objective, data-driven assessment of the battery’s condition. Additionally, inquiring about the vehicle’s charging history can provide clues. A battery that has been predominantly charged using high-power DC fast chargers may show more degradation than one that has been consistently charged at a slower Level 2 rate at home.

This knowledge empowers you to look beyond the shiny exterior and assess the true health of the vehicle’s heart, ensuring your investment is a sound one.

How to Design Products That Can Be Repaired in 5 Minutes?

The philosophy of Design for Disassembly extends naturally to a more immediate benefit: repairability. In a traditional, “sealed unit” battery design, the failure of a single cell or a minor component within the BMS can render the entire multi-thousand-dollar pack useless. The only option is a full, costly replacement. This is not only uneconomical but also deeply unsustainable. The alternative is a move toward modular architecture, a design principle that could make many battery repairs a quick and straightforward process.

The key is to treat the battery pack not as a monolithic black box, but as a system of interconnected, swappable components. As one battery design engineering expert noted in an industry analysis, the goal is to emulate the user-serviceable nature of a desktop PC rather than a sealed laptop. This requires a fundamental shift in design thinking.

Champion Modular Architecture: Use the analogy of a desktop PC vs. a sealed laptop. A modular battery pack with swappable cell groups, accessible connectors, and a separate BMS is the key.

– Battery Design Engineering Expert, Industry Analysis on Modular Battery Design

In a modular battery pack, cells are grouped into smaller, manageable modules. If one module degrades faster than the others, it can be individually unbolted, unplugged, and replaced in minutes, rather than junking the entire pack. The BMS, another common point of failure, can be designed as a separate, accessible unit. Using standardized connectors and fasteners instead of permanent adhesives is the lynchpin of this approach. This not only facilitates rapid repair but also simplifies the process of upgrading the battery pack with newer, more advanced cell chemistry in the future, extending the life of the vehicle itself.

By prioritizing modularity and accessibility, engineers can create products that are not only easier to maintain but also inherently more valuable and less wasteful over their entire lifespan.

Key Takeaways

- Ethical Loop: The human rights issues in cobalt mining create a moral and economic imperative for a “closed-loop” system, where recycling directly reduces the need for new extraction.

- Waste as a Resource: An EV battery below 70-80% capacity is not “dead.” It becomes a valuable asset for “second-life” applications like home energy storage, with the potential to meet the entire global demand for stationary storage.

- Design is Destiny: True sustainability is determined on the drawing board. Designing batteries for easy disassembly and repair (modularity, accessible connectors) is the key to unlocking efficient recycling and a longer product life.

How Can Small Businesses Profit From Waste Streams?

The transition to a circular economy for batteries is not just an environmental mandate; it’s one of the most significant emerging business opportunities of the 21st century. The sheer volume of end-of-life batteries from EVs, consumer electronics, and power tools represents a massive, predictable, and highly valuable “urban mine” of resources. For entrepreneurs and small businesses, this waste stream is a goldmine waiting to be tapped, with a projected market value for EV battery recycling expected to reach approximately $19.3 billion in the coming years. This creates a powerful economic engine that drives sustainable practices.

The opportunities exist all along the value chain. Small businesses can specialize in logistics, safely collecting and transporting used batteries. Others can focus on diagnostics and grading, developing sophisticated systems to test batteries and sort them for either second-life repurposing or recycling. On the repurposing front, companies can design and sell home energy storage systems built from used EV modules. The most capital-intensive but potentially most lucrative area is in the recycling itself, where innovative hydrometallurgical processes can yield high-purity materials ready for the market.

This isn’t a theoretical future; it’s happening now. Companies are already building profitable business models centered on transforming electronic waste into high-value raw materials.

Case Study: Redwood Materials’ Profitable Recycling Model

Founded by Tesla co-founder JB Straubel, Redwood Materials provides a powerful example of this new economy. The company’s facilities process a vast array of lithium-ion batteries from dead smartphones, power tools, and EVs. Using an advanced hydrometallurgical process, Redwood can recover over 80% of the lithium and up to 98% of the nickel, copper, and cobalt. The final output is not a mixed metallic alloy, but barrels of pure, battery-grade materials like lithium carbonate, ready to be sold directly back to battery manufacturers. This demonstrates that a closed-loop recycling process is not just a science project but a scalable and profitable enterprise today.

By creating a strong economic incentive to collect and process used batteries, the market itself becomes the most powerful force for ensuring these materials are managed responsibly, transforming a potential environmental crisis into a thriving new industry.

Frequently Asked Questions About What Happens to Your EV Battery When It Dies?

What percentage of battery capacity indicates it’s time for replacement?

While a battery is often considered for replacement in an EV when its capacity drops below 70-80% of its original state, it’s not the end of its life. An older EV battery may no longer be suitable for long-distance driving but could still have enough storage capacity to find a valuable second life in a stationary application, like home energy storage.

How can I check the actual battery health beyond the dashboard display?

Use OBD2 (On-Board Diagnostics) diagnostic tools with specialized apps to access the Battery Management System’s State of Health (SoH) data directly. This provides more accurate and objective information about the battery’s true degradation level than the range estimates shown on the dashboard, which can be affected by recent driving habits and temperature.

What are the signs of excessive DC fast charging damage?

The most reliable way to check for damage is to request the vehicle’s charging history if available. Look for patterns of frequent and repeated DC fast charging sessions. While convenient, overuse of high-power fast charging can accelerate battery degradation compared to the slower, more gentle charging process of a regular Level 2 home charger.